So you’re you, yes? A person of conservative or traditional or simply unloony views walking your campus with your head in...

To Conservatives Who Want to Save Culture

At the heart of being a conservative there are two agreements—an agreement we make with the people of the past and an agreement we make with the people of the future.

With the people of the past we agree to sustain the efforts they made to create the world we live in today. We make an equally important agreement with the people of the future that we will pass our world and its culture along to them in better shape than we found it.

These agreements are not promises to freeze culture and repeat it. To attempt to do so would be to pervert human nature, which has always been inquisitive and inventive, always seeking out better ways to create those things that sustain us. Conservatives are not afraid of new ideas, but they are careful that the introduction of them is done mindfully, with consideration of the impact these things may have on the cherished features of our culture. Will they prove truly beneficial in the future or harm the things that we prize?

It is easy to forget this contract and to pretend that the past doesn’t matter, and some idealists even propose to destroy the old ways and replace them with Utopia. This impulse to “smash it up” is driven by awareness of the failings of our civilization. But the impulse to destroy ignores the strengths of our civilization, and we cannot surgically remove the bad things without facing the impact such an intervention would have on the good things. Sometimes change has unintended consequences.

The past is valuable. If our ancestors had not defended the positive features of our society, if they had not fought for what they believed was important, and if they had not built the traditions that acknowledge our shared heritage, then none of us would understand our own identities as members of nations, of ethnicities, or of cultures. What are conservatives hoping to conserve if not culture?

Emulation vs. Imitation

Conservatives learn from history but approach it with a critical attitude. By knowing our history we may avoid repeating past mistakes. It is important to remember that history may not repeat itself but, as Mark Twain is reputed to have said, it often rhymes. We must be careful that we don’t allow good intentions to take tyranny to tea.

Tradition is fluid. By knowing what has happened in the past, we may use it to shape the present and the future. The flurry of excitement about what should replace the roof of Notre Dame cathedral illustrates this beautifully. Some ridiculous proposals have been made, including a glass-and-steel greenhouse canopy, a thing resembling a spaceship, and a plan to replace the entire roof with a gigantic stained-glass window.

Fortunately the French Assembly has sensibly decided to restore the building to its former appearance. But that commitment almost certainly does not mean a perfect duplication of the old, for whoever is hired to restore the great church’s burned steeple and lead-covered oak timbers will doubtlessly improve upon the original design to ensure that the fiery destruction of this symbol of our heritage will not happen again. The old will be reborn. It’s important to remember that the fallen spire was a nineteenth-century replacement of the original, which was first built in the thirteenth century. The new tower will continue the tradition of restoration and renewal at Notre Dame and remind us that all great ancient buildings are constantly in a state of rebuilding and repairing. Conservation and restoration are like architectural conversations, in which the old uses of the building meet with its new ones, and compromises are made to decide how both can best be served.

Conservation is really a matter of emulation, which is not the same as imitation. When we imitate, we duplicate, we fail to make any improvement, and we merely counterfeit the original. A copy is a dead thing, a forgery. We don’t value copies. When copies of works of art are identified, we remove them from museum collections because they are unworthy of the admiration we offer authentic things.

To emulate the past, then, is neither to fake it by making pastiches of its products nor to copy it slavishly; instead, it is to build respectfully upon the examples of the past and gift them to the people of the future. Emulation is found when creative people use the best of the work of past masters as foundations, making new works that feed the culture of their own time but that also honor the past.

As with architecture, traditional art and culture must always be cared for and repaired to keep them in good condition. We have the good fortune to live in a period in which truly extraordinary paintings and sculptures are being produced using the old traditions of Western studio art. One of the great joys of the early twenty-first century is seeing this great art emerging reborn from the rubble of the twentieth century. The representational art movement is growing from a lively and exciting community of artists and collectors. Representational art is made up of paintings and sculptures that look like real things—“stuff that looks like stuff.” Its vigor is fed by three important wellsprings: the traditions of Western art, the skill-based studio techniques of nineteenth-century ateliers, and twenty-first-century popular culture.

Examples of “Conservative” Art Today

Although twentieth-century avant-gardists attempted to invent a new kind of abstract art for an imaginary Utopia, representation is a more direct and effective way of expressing meaning, and has come back to the foreground of the art world in the twenty-first century.

That iconic representational paintings like Botticelli’s Birth of Venus and Da Vinci’s Mona Lisa remain huge draws for tourists speaks to the power of representational art. But these masterpieces are not stuck in the past, they are part of a living tradition that gives contemporary representational painters and sculptors the rock upon which to build their work.

The skill-based studio techniques of the nineteenth-century salon are thriving in the hands of artists trained at the atelier art schools that have emerged in every major U.S. city in the past twenty years. Painters and sculptors who complete programs at these new schools are exceptionally skilled at producing work that continues the rich lineage of tradition.

But what differentiates their work from the art of the past?

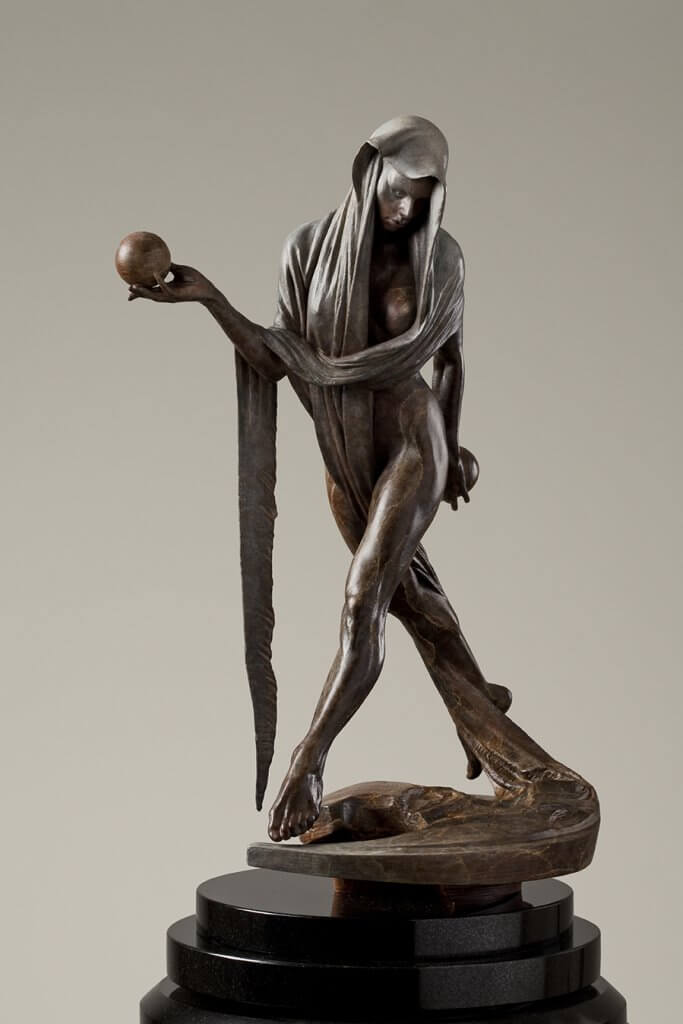

You would not mistake this wonderful sculpture, a contemporary masterpiece by Richard MacDonald, with either a Greek sculpture or an Italian Renaissance statue. MacDonald uses traditional techniques that he learned from the hands of his teachers, who learned them from the hands of their teachers, following a initiatory lineage of knowledge that doubtlessly dates back to Ancient Greece. But his sculptures are absolutely contemporary. He takes the wisdom of the lineage as the foundation for his imagery, which is informed by his creative imagination, and uses the muscular athleticism of Cirque du Soleil performers as his models.

Developing alongside popular films and video games, fantasy and science fiction art has evolved dramatically to become a new genre within representational art, called imaginative realism. Imaginative-realist artists like MacDonald use traditional studio techniques to create paintings and sculptures of things that don’t exist. In addition, they create imagery that should prove appealing to conservatives because it is born from the tradition of Western art history yet is unique to our time. The imagery of imaginative realism is powerful and visually stunning, and fertile ground for experimenting with interesting ideas. It has become one of the most exciting, flourishing cultural innovations in the art world.

There are many excellent imaginative-realist painters. Here’s an example of an image created by a genius of the movement.

Odd Nerdrum paints in a style comparable to Rembrandt’s, but you would not mistake one of his pictures for one of the Old Master’s. Their techniques may be similar but the composition and content are extraordinarily different. Nerdrum paints refugees from the modern world—topics Rembrandt would never have conceived. Although rigorous in his use of live models, Nerdrum crafts compositions informed by photography that Rembrandt could never have imagined. Nerdrum emulates the work of Rembrandt and turns it into something new while honouring the long tradition of painting. His paintings are informed by themes familiar to fans of fantasy films—itinerant exiles wander through a post-apocalyptic landscape, wearing medieval clothing—and uses alchemical imagery to create a mysterious mood.

Pay It Forward

So far I have described the agreement with the people of the past but have said little about the agreement with the people of the future. How do we improve our culture and pay it forward to them?

This is easiest for the people involved in artistic production, for their products make manifest their hope for the future. But cultural works depend on the relationship between their makers and their consumers.

For consumers of culture, the agreement to conserve it is a promise to participate in it, not stand idly by as others direct the cultural course. To participate in cultural conservation means to be engaged in the arts, to be active patrons of and contributors to them. True conservatives are philanthropists. True conservatives visit art galleries and read novels, watch movies and go to plays, purchase paintings and sculptures by artists who emulate traditional technique, use social media to bring attention to interesting work, and support such work financially.

Most important, conservatives make their preferences known and explain why they like the cultural products that resonate with them. By supporting the arts that satisfy their interests and expectations, conservatives build and maintain the culture they desire as a gift to their children, and to their children’s children.

Cultural conservation demands action!

Michael J. Pearce is a figurative artist and author of “Art in the Age of Emergence.” In 2012 he founded The Representational Art Conference.

Article image by Svetlana Pochatun via Unsplash. Artist images used with permission.

Get the best of intellectual conservative thought

J.D. Vance on our Civilizational Crisis

J.D. Vance, venture capitalist and author of Hillbilly Elegy, speaks on the American Dream and our Civilizational Crisis....