So you’re you, yes? A person of conservative or traditional or simply unloony views walking your campus with your head in...

Socialists in the Kool-Aid

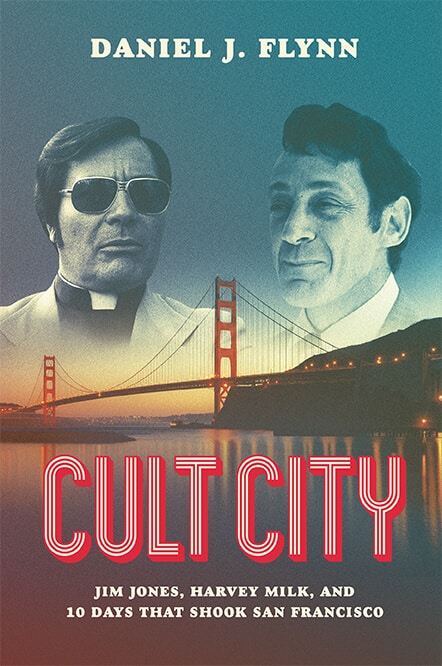

Forty years ago, the name Jim Jones and the idea of “drinking the Kool-Aid” became indelibly etched in our collective memory as the world learned of a mass cult suicide in the jungles of South America. Movies and books have been written about Jones, but a key element of his story remains in the shadows: his career in San Francisco as a preacher and politico, courting and seducing some of the most powerful Democratic Party players in that weird and wild city, including a man who has become a cultural icon and hero to many, Harvey Milk. Daniel J. Flynn, author of Blue Collar Intellectuals and Intellectual Morons, has written a deeply researched and chilling account of the strangest of bedfellows—Cult City, which hits bookstores today. Here is an excerpt.

The advertisement billed the December 2 benefit gala as “A Struggle Against Oppression.” Scheduled speakers included rising Assemblyman Willie Brown as the master of ceremonies and funnyman Dick Gregory as the keynote. Supervisor Harvey Milk and other movers and shakers of an oft moved and shaken city crammed their big names into a small font on the flyer. For the bargain of $25—and “tax deductible” at that—influence seekers could seek to influence the mighty of a great American city. In addition to mingling with such power brokers as Brown and Milk, they could corner Sheriff Eugene Brown, physician and newspaper publisher Carlton Goodlett, and Supervisor Carol Ruth Silver at San Francisco’s Hyatt Regency. And doing well meant doing good. The dinner’s proceeds subsidized the Peoples Temple Medical Program.

The Hyatt ballroom remained empty on December 2, 1978. Two weeks earlier, the small staff of the Peoples Temple Medical Program had mixed cyanide with Flavor Aid and administered the poisonous, sugary elixir to hundreds of people in faraway Guyana. The smiling seniors and racial rainbow of children touting the wholesomeness of the agricultural commune in the fundraiser’s promotional literature rotted in piles in the steamy South American jungle. On an airstrip in nearby Port Kaituma, five people, including Congressman Leo Ryan, lay dead, gunned down by Peoples Temple assassins. Others, including future congresswoman Jackie Speier, State Department official Richard Dwyer, and San Francisco Examiner reporter Tim Reiterman, nursed bullet wounds. In Guyana’s capital city, a former Harvey Milk campaign volunteer slashed her children’s throats.

The Reverend Jim Jones, the darling of the San Francisco political establishment, orchestrated the murders and suicides of 918 people on November 18, 1978. The man-made cataclysm represented the largest such loss of civilian life in American history until 9/11 and the largest mass suicide of the modern age. Nothing before or after struck Americans as so bizarre.

The event shocked the world. But the small world surrounding Peoples Temple predicted it—loudly and repeatedly. Not every utterance from Jonestown’s namesake, after all, proved as cryptic as the one block-quoted on the “Struggle Against Oppression” promotional literature: “We have tasted life based on total equality and now have no desire to live otherwise.”

In the chaotic aftermath of the carnage, the Temple’s aggressive communism and evangelical atheism got lost in translation from the Guyanese jungle to bustling urban newsrooms looking to get the story first rather than right.

A New York Times article alleged that “Mr. Jones had preached a blend of fundamentalist Christianity and social activism.” The Associated Press called the people of Peoples Temple “religious zealots.” Walter Cronkite, the most trusted man in America, described Jim Jones as “a power-hungry fascist.” Comedian Mort Sahl explained on his radio show days after the massacre, “The exercise in Guyana was a fascist exercise, no matter what the label on the can. Socialists don’t do that.” Neither a half-hour CBS special called “The Horror of Jonestown” nor an NBC report titled “Jonestown, November 1978: How Could It Happen?” raised the issue of the group’s Marxism.

Not everyone accepted the initial narrative. One fundamentalist minister, in a letter to the editor of the Boston Globe, objected to a California News Service article that termed Jones’s flock a “fundamentalist congregation.” Pravda, the official newspaper of the Soviet Communist Party, seized an opportunity to ridicule the West by noting that “the United States news media are trying to convince Americans as well as the foreign public that the deaths were the action of wild religious fanatics.”

Pravda and the Globe’s fundamentalist correspondent—strange bedfellows—were right. The supposed religious fanatics of Jonestown had hosted a Soviet delegation, taught Russian to residents in preparation for a mass pilgrimage to the place Jim Jones dubbed the group’s “spiritual motherland,” and willed millions of dollars to the Soviet Union. Peoples Temple goons confiscated Bibles reaching Jonestown from the United States. Jonestown celebrated December 25 as Revolution Day. They sang songs about Jim rather than Jesus. Jones openly denounced the “stupid Skygod.” When the jungle community ran out of toilet paper, Jones distributed Bibles for bathroom use—a practice hitherto unknown among fundamentalist Christians.

The initial rush of information confused falsehood for fact to such an extent that many gleaned an impression of the Temple diametrically opposed to reality. Jonestown, a jungle citadel of evangelical atheism and militant socialism, strangely became a cautionary tale about the dangers of evangelical Christianity.

The Nation offered one of the few reality checks. “The temple was as much a left-wing political crusade as a church,” the weekly offered. “In the course of the 1970s, its social program grew steadily more disaffected from what Jim Jones came to regard as a ‘Fascist America’ and drifted rapidly toward outspoken Communist sympathies.”

Distortions endure. The cover of Rebecca Moore’s 2009 book Understanding Jonestown and Peoples Temple, a follow-up to A Sympathetic History of Jonestown and In Defense of Peoples Temple, shows pictures of a white teacher patiently instructing black children, jubilant multiracial chefs preparing a dinner, an elderly man receiving medical care, and an industrious boy spinning a pottery wheel. Moore insists that the commune’s “reality was not completely at odds with the façade” it presented to the world.

“If anything,” Julia Scheeres maintains in 2011’s A Thousand Lives: The Untold Story of Hope, Deception, and Survival at Jonestown, “the people who moved to Jonestown should be remembered as noble idealists. They wanted to create a better, more equitable, society. They wanted their kids to be free of violence and racism. They rejected sexist gender roles. They believed in a dream.”

Most people who live in a nightmare do.

The beliefs of Jim Jones and Peoples Temple—political, spiritual, and otherwise—ultimately proved a terrible embarrassment to allies; their actions, more so. Politicians, journalists, and others distanced themselves from the Temple.

The situation was far different when Jones was alive. During Peoples Temple’s heyday, Huey Newton, Jane Fonda, and Angela Davis heaped praise on the clergyman. A Los Angeles newspaper named Jones “Humanitarian of the Year.” The prominent interfaith organization Religion in American Life named him one of the nation’s one hundred outstanding clergymen, feting him at New York’s Waldorf Astoria. The president of CBS talked to Jones about producing a TV documentary on Peoples Temple.

Peoples Temple offered the political class votes and volunteers. In return, the Temple received legitimacy. Jones held court with future first lady Rosalynn Carter; two vice presidents, Nelson Rockefeller and Walter Mondale; Governor Jerry Brown and Lieutenant Governor Mervyn Dymally of California; and many other political figures. Willie Brown compared Jones to Albert Einstein and Martin Luther King Jr. Local media speculated that Jones could abandon the pulpit for the best office in City Hall.

Just nine days after the live-action horror movie in Guyana, another tragic event shook San Francisco: Supervisor Dan White murdered fellow supervisor Harvey Milk and Mayor George Moscone in City Hall. As with the Jonestown massacre, myths cloud our understanding of these assassinations.

In life, the assassin served as a protégé of future U.S. senator Dianne Feinstein, a public-employees union activist, and a friend and occasionally an ally of Harvey Milk. He represented blue-collar San Francisco Democrats as a blue-collar San Francisco Democrat. But after murdering fellow Democrats Milk and Moscone, the surely disturbed Dan White morphed into a “disturbed right-wing supervisor.”

White’s victims experience a similar treatment of revisionist history. Moscone and Milk, tightly linked to Peoples Temple in life, strangely became untethered from the group in death. Moscone probably owed his election as mayor to Jim Jones and Peoples Temple. As thanks, the mayor appointed Jones to an important city post, making him chairman of the San Francisco Housing Authority Commission.

Harvey Milk became one of Jones’s most effusive advocates. He sent gushing letters to Jones and lobbied prominent leaders on behalf of Peoples Temple. Milk sent the president of the United States a letter so fawning that, in the words of one Temple chronicler, it “reads as if it were written by a Temple publicist.” To the prime minister of Guyana, Milk declared, “Such greatness I have found at Jim Jones’ Peoples’ Temple.”

Before Peoples Temple drank Jim Jones’s Kool-Aid, powerful people in San Francisco did. Harvey Milk imbibed most enthusiastically.

The popular treatments of Milk’s life do not leave this impression. In the Academy Award–winning movie Milk, starring Sean Penn, the Peoples Temple preacher, who proved crucial to Milk’s political rise and whose rise crucially depended on Milk and other Bay Area pols, appears nowhere. Leading biographies of Milk and Jones barely mention how the two San Francisco leaders helped each other.

Whereas chroniclers whitewashed Jim Jones before the events of November 1978, they whitewashed Harvey Milk after them. A man who had a long romantic relationship with a runaway he picked up at age sixteen now gives his name to a state holiday celebrated in California’s schools. A pioneer in the practice of “outing” and a constant practitioner of in-fighting with other gays now serves as a homosexual Martin Luther King figure idealized to the point of distortion. A politician who served honorably in the military subsequently won praise for a nonexistent dishonorable discharge that fuels a victimhood storyline. If Jones’s death eventually unearthed the truth about him, Milk’s unleashed a caricature often at odds with the facts.

In addition to uncovering archived material unavailable to or overlooked by previous researchers, this book includes scores of interviews providing a fresh perspective that upends what we think we know about the events of November 1978. The figures interviewed include Jim Jones’s onetime chief lieutenant; one of only three still-living survivors of the Jonestown tragedy present when the killings began; classmates of Harvey Milk and a playmate of Jones; a follower who plotted to kill Jones; the police officer who arrested Dan White; people shot by Peoples Temple enforcers; colleagues and rivals of Milk, White, and Moscone; and numerous other eyewitnesses to history largely unheard until now. These voices tell an untold story.

Characters propelled the events of November 1978. A unique setting allowed the tragedy to occur.

In San Francisco, the tie-dyed, Day-Glo 1960s morphed into a grimmer 1970s scene populated by serial killers, mad bombers, political assassins, and atavisms advertising the excesses of the previous era in gait, speech, and stare. In the Star Wars bar scene of 1970s San Francisco, Peoples Temple fit in more than it stood out. Yet the thumbnail tale of the Temple generally fixates on how so many could fall for such a charlatan in Guyana. What about San Francisco? There Herb Caen, Paul Avery, and other star journalists fawned over Jones, clergy celebrated him, and elected officials spoke of him as though speaking of a supernatural force and not a mere man.

Many crooked preachers fool the flock from the pulpit. Jim Jones suckered an entire city, or at least that portion of it holding the most sway.

The tragedy birthed in Guyana was conceived in California. One of the midwives was Harvey Milk. He depicted Jim Jones as a saint, Jonestown as an Eden, and the Temple’s opponents as loathsome. He wrote lobbying letters to more powerful political leaders touting the Temple and its leader. Though generally phobic toward organized religion, he described his experiences attending Peoples Temple in ecstatic terms. Jones incentivized such treatment by producing campaign volunteers, promoting the politician, and providing material support. More important, he preached a message Milk wanted to hear: Jones used the pulpit to extol homosexuality when other religious figures regarded it as a sin. Milk chose to see the beautiful illusion and not the insanity staring him in the face.

People with worse educations and fewer opportunities did so at greater penalty. Never speaking with much of a megaphone in life, and silenced in death, the victims became victims all over again in the aftermath. The mighty back in San Francisco washed their hands of any complicity. The narrative stressed a band of kooks isolated in the jungle. It largely bypassed the alliance between Jim Jones and Harvey Milk, George Moscone, and other local leaders.

Reasons specific to San Francisco set the tragedy in motion. So did ones universal within human nature. The Temple’s influential friends overlooked evidence of severe wrongdoing to actively promote Jim Jones. The glorious vision Jones elucidated obscured the dark reality. The attempt to create heaven on earth instead produced a hell.

Jones found allies among the powerful; he found devoted followers in the pews. A charismatic preacher, he attracted thousands to his San Francisco services and exerted an extraordinary hold over his Peoples Temple followers. They called him “Father” and viewed him as God. The deeper they rooted their support for Jim Jones, the more difficult they found it to dig themselves out of the hole. The same phenomenon that damned the judgment of the powerful in San Francisco doomed the powerless in Jonestown. The cover-ups, the prioritizing of correct politics over right conduct, and the fidelity to the narrative when it clashed with facts led to the faithful’s demise and characterized the mentality of their boosters safe in San Francisco. And four decades later, the scrubbing of reality to produce a politically cleaner version continues. People who bowdlerize the events of 1978 strangely wonder how people in 1978 could have bowdlerized events in 1978.

In the cases of Jim Jones and Harvey Milk, an end-justifies-the-means mentality erased faults and emphasized good deeds. Then, politicians enjoying Peoples Temple support dismissed specific reports from numerous eyewitnesses of serious criminal conduct by Jim Jones. Now, Harvey Milk’s admirers erase his close alliance with Jim Jones. To note the tall tales he told about himself and others to further a persecution narrative, the outing of a friend for political advantage, and his predatory relationships with teens and young men all mark the messenger as indecent. This book confronts the noble lie.

Jones did no wrong in life. Milk proved infallible upon death. The politician and the preacher, a saint and a devil in their afterlives, walked the earth as human beings.

Daniel Flynn is the author of five books, including Blue Collar Intellectuals: When the Enlightened and the Everyman Elevated America, and Intellectual Morons: How Ideology Makes Smart People Fall for Stupid Ideas. A senior editor of the American Spectator, he has written for the Los Angeles Times, the Chicago Tribune, the Boston Globe, the New York Post, City Journal, and National Review. He lives in Massachusetts.

Get the Collegiate Experience You Hunger For

Your time at college is too important to get a shallow education in which viewpoints are shut out and rigorous discussion is shut down.

Explore intellectual conservatism

Join a vibrant community of students and scholars

Defend your principles

Join the ISI community. Membership is free.

J.D. Vance on our Civilizational Crisis

J.D. Vance, venture capitalist and author of Hillbilly Elegy, speaks on the American Dream and our Civilizational Crisis....